Today’s NHL has a multitude of talented players from all over Europe and North America. Players from former Eastern Bloc countries make up a huge portion of the stars of the League.

However, this wasn’t always the case, as the USSR heavily guarded their hockey programmes. They certainly didn’t allow players to choose where they wanted to play, and because of this, some players took matters into their own hands.

Hockey Divided

Due to the divide caused by the Cold War, very few Russians and members of the Eastern Bloc ever made it across to the NHL. To the majority of players, this was the highest standard of Hockey. Those that did make it across were part of token gestures by the USSR, and were often forgettable and failed to have any kind of impact.

Super Stan

The trailblazer for Hockey players from the Eastern Bloc playing in the NHL, Stan Mikita, moved to the United States as a young boy. After Czechoslovakia became Communist, Mikita’s parents didn’t want their son growing up under the regime. A dynamic and tough forward, Mikita went on to be the record points scorer for the Chicago Blackhawks.

In the words of Peter Stastny ‘he put the NHL up to the highest echelon in Slovak thinking’. This led others to think about what they could achieve if they played in North America.

Not for the Faint Hearted

Though Mikita was a hero across the USSR and particularly Czechoslovakia, to follow in his footsteps wasn’t as simple as moving to the US in order to play in the NHL. Few players were able to make the move as they feared for the safety of their families.

‘Defecting’ from the USSR would mean they could never return, and would have nothing to fall back on if they were unsuccessful in North American Hockey. This prevented many of the great talents of the Soviet Hockey programme, and the hockey programmes around the Eastern Bloc, from ever playing on the biggest stage.

A Noble Cause

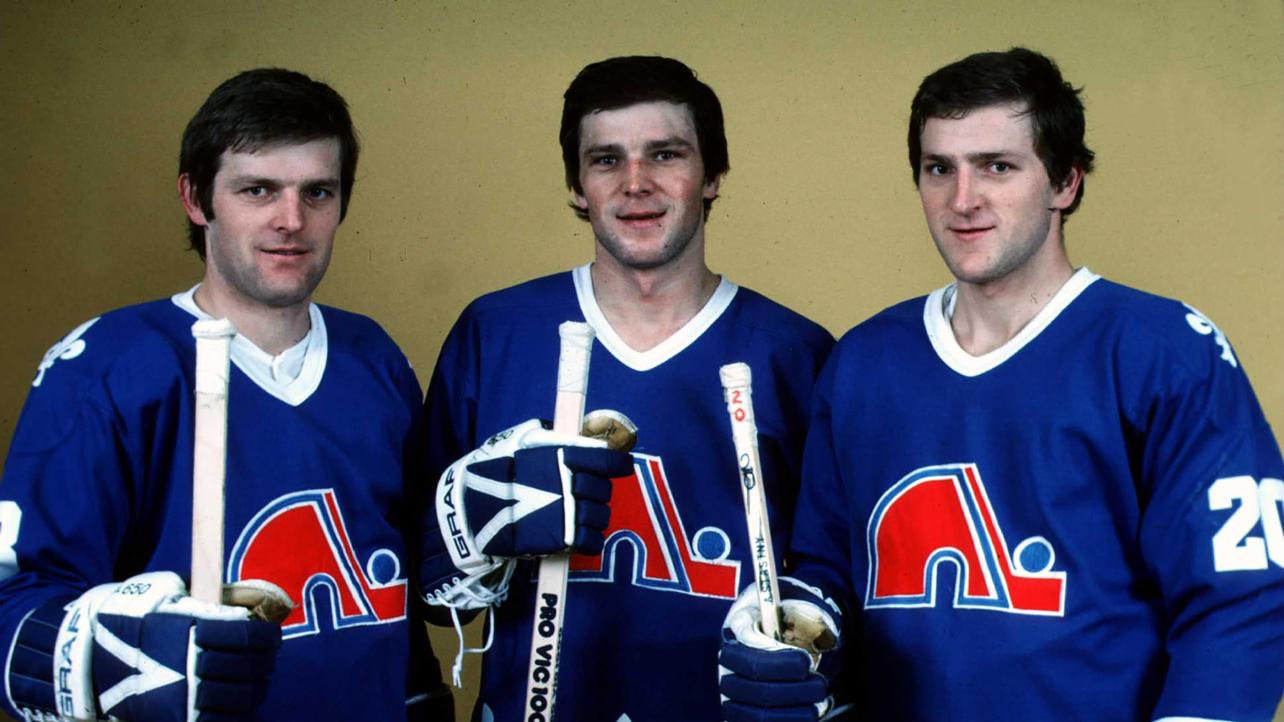

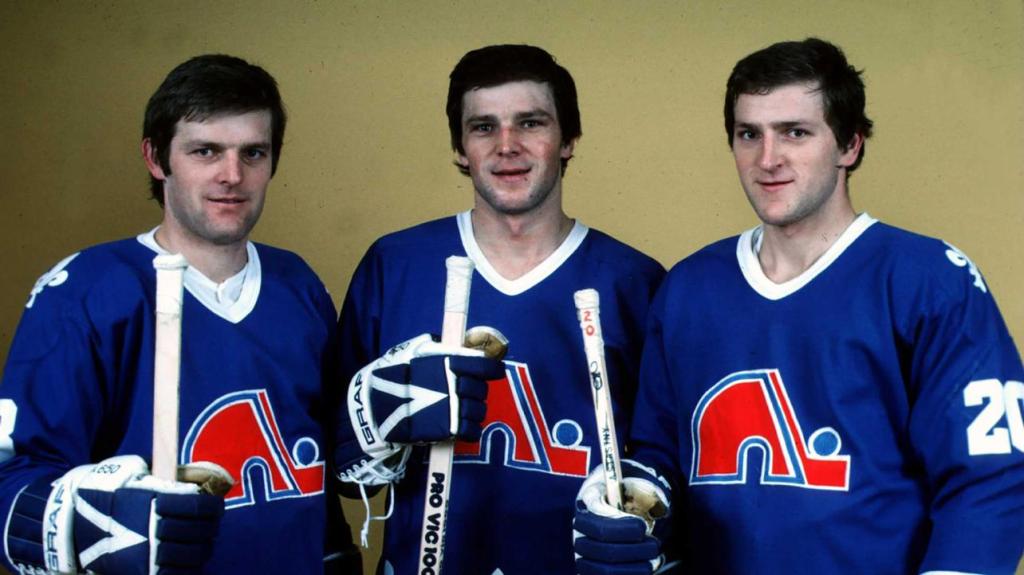

Peter Stastny and his two brothers, Anton and Marian, can be seen as the largest early case of a defection to play in the NHL. In an interview with TSN, Peter stated that he was motivated by the thought of his children growing up under a Communist led regime. ‘I didn’t want my children to grow up with a split personality — values taught at home and different values taught by the regime’.

The Importance of Planning

The Czech national team had not played well at the 1980 European Championships in Vienna, and so Peter contacted the Quebec Nordiques. He informed them that he and his brother wanted to leave for Canada.

Marcel Aubut, CEO of the Nordiques, and personnel director Gilles Leger immediately flew to Innsbruck, instead of Vienna, in an attempt to avoid being followed by Czech or Russian security services. According to an article soon after the events by Hal Quinn ‘Leger had been working on the defection since November 1976,’ thus proving the difficulty and complexity of the task Leger and Aubut had to complete.

The plan was to get the two brothers and Peter’s heavily pregnant wife (Darina) on a flight to Amsterdam and then to Canada. They decided the best first step was to get them to the Canadian Embassy in Vienna, and while there, they could apply for political asylum.

Difficulty came with the presence of the Czech secret service providing security for the team. Aubut recounted one previous attempt to bring the brothers to North America around the Winter Olympics; ‘the police around the Russian and Czechoslovakians were so thick we couldn’t get within 100 feet of them.’

A Plan Comes Together

After the brother’s final game, Aubut and Leger rushed them and Darina into a car and took them straight to the embassy. The Czech security services reportedly had guns drawn on the defectors as they made their hasty exit. The embassy then protected them as they gained political asylum and were taken to the airport. Aubut stated that the success of the defection ‘was like a victory by capitalism over communism’.

A Roaring Success

The oldest Brother, Marian, felt he couldn’t leave Czechoslovakia due to the fact he would have to leave his wife and three children behind. However, Peter, his wife and Anton fled for North America. The two picked up $1 million 5-year contracts in Quebec, and made the Nordiques a force in the NHL. Peter scored 109 points in 77 games in his rookie season, and Anton 85 points in 80 games.

Meanwhile, as was reported in the New York Times in 1981, Marian was suspended from the Czechoslovakian national team, and was out of Hockey all together. In an interview at the time, Peter alluded to the shady nature of this by saying that the official reason for the punishment was ‘he had difficulties getting along with the coach. But I think they are reprimanding him for our departure.’

Marian would join up with the Nordiques not long after, and the fairy tale story of the defected brothers playing for the same team, on the same line, was complete. Though they would never have the ultimate ending of winning a Stanley cup, they set an example for European players coming to the NHL.

A Legacy of Greatness

Peter’s legacy has carried on today, with a great number of lasting impressions left by the Czech:

- He was the highest scoring player not named Wayne Gretzky across the 1980s, scoring 1059 points across the decade

- His son Paul, plays as first line centre for the Vegas Golden Knights

- the Stastny brothers built upon the legacy of one of the greats of Hockey, Stan Mikita, providing inspiration for so many young Europeans looking to find their way in Hockey

- Peter was honoured with a place in the Hockey hall of fame, after an NHL career of 977 regular season games in which he scored 1239 points.

- He was awarded a spot in the NHL’s top 100 greatest players of all timein 2017, to commemorate 100 years of the NHL

Are there any other ways in which the Stastny’s impacted the world of hockey? Comment below with your ideas.